One would expect that EU chemicals legislation would target chemicals with the highest risk towards humans and nature. Instead, it seems that regulation is very much dictated by economic interests. Today, ChemSec and the FRAM Centre at the University of Gothenburg can show that if member states stand to lose money by the regulation of certain chemicals, these substances are less likely to be passed through the legal bodies of the EU.

Looking back at all chemical propositions for the Candidate List, as well as who proposed them, several things become obvious. The most glaring being that member states avoid proposing substances that play an important economic role within the country’s own borders.

EU countries want to see toxic chemicals regulated – as long as someone else is paying for it

If there is a notable national industry whose profits are based on a certain chemical, member states tend to avoid proposing this chemical for the Candidate List regardless if the chemical has any health or environmental concerns.

Out of the 155 chemicals proposed by member states, only a third were submitted by member states that actually produce the chemical in question. The unwillingness to propose chemicals that are produced nationally is particularly striking in the cases of Sweden, Austria, Norway, Belgium, and Denmark.

How it works

- The EU Candidate List is one of the most important steps to move industry away from hazardous chemicals in products and processes.

- A chemical needs to go through several steps to end up on the list, including evaluating committees and public consultations.

- Only member states and the Commission (through the European Chemicals Agency, ECHA), can propose chemicals for the list.

The same tendency can be seen in the public deliberations that take place after the chemicals have been proposed.

During deliberations, stakeholders (national agencies, industry, NGO:s, academia etc.) are invited to comment on the specific chemical and either support or advise against placing it on the Candidate List. A majority of supporting comments originate from countries that do not produce the chemical. The opposite is also true; non-supportive comments come from countries that do produce it.

Cancer-causing chemicals are the exception to the rule

In the cases where countries do propose chemicals that are produced nationally, a majority are motivated by concerns for carcinogenicity and exposure to the general public – something that seems to trump the interest to protect national industry. In fact, most propositions overall relate to chemicals with cancer properties (CMR), and in contrast, very few substances with persistence, bioaccumulation (vPvB, PBT) and/or hormone disrupting properties (End. Disr.) have been proposed for inclusion on the Candidate List.

Many chemicals targeted by legislation are not used in the EU

Moreover, 65 of the total 155 chemicals proposed by member states are not even produced or used in the EU (other than in such small amounts that it doesn’t require notifying authorities).

But why are countries suggesting chemicals for the Candidate List even if they are not used on the European market?

A speculative answer is that by proposing known problematic chemicals, member states can show that they are capable of political action without hurting economic interests inside the bloc. The fact that about 80% of the proposed chemicals are used by no more than five European countries give further weight to this speculation.

Another explanation for the willingness to propose non-used chemicals could be that future imports of such chemicals could possibly hurt European industry. It is widely accepted that if a chemical sees legislative action it is a major market driver for suitable alternatives. With this logic in mind, it is perhaps not surprising that Germany – whose industry invested heavily in phthalate-free plasticizers – has proposed several phthalate-based plasticizers for the Candidate List even though they are not used in the EU.

However, there are definitely legitimate reasons for proposing chemicals that are not used in the EU. For example, it is a first step towards restricting direct imports of articles, such as consumer goods that contain these chemicals.

The chemical lobby is a major force in European politics

Even though the EU’s chemicals framework REACH is organised in a way that allows for stakeholder input – through for example public consultations – evidence suggests that industry is far better represented in these processes compared to authorities, academia and public interest groups.

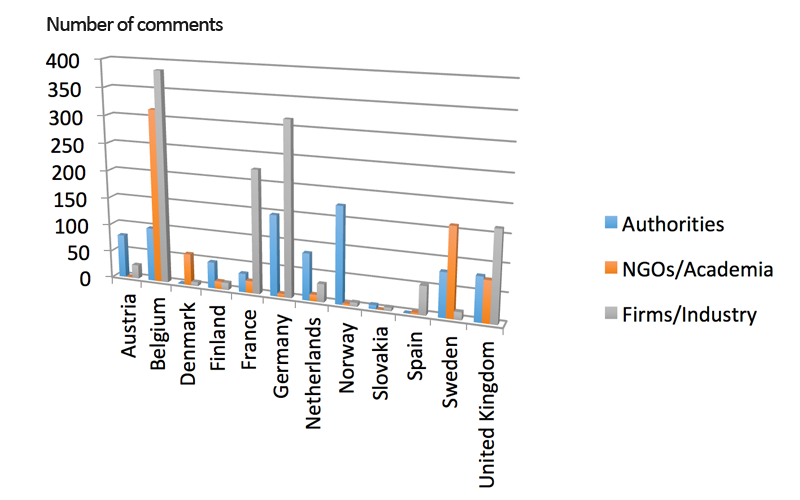

Looking at the deliberations of chemical propositions for the Candidate List, industry comments amount to almost 50% of all comments, authorities to about 29% and NGOs and academia to about 21%. When looking at where the comments originate from, it is clear that the largest chemical producing countries are heavily overrepresented.

Furthermore, about 90% of the comments from non-industry stakeholders are supportive of placing the chemical in question on the Candidate List. This paints a striking difference to the measly 8.5% of the industry comments that are supportive.

Back in 2006, before the chemical legislation REACH entered into force, the EU Commission estimated that about 1,500 substances with toxic properties would be eligible for the Candidate List. But as of January 2020, it includes only 205 substances. Looking at the facts presented in this article, it seems obvious that the design of the political process has favored pro-industry interests.

ChemSec note: In this article, the term “production”, might also include import from non-EU countries.

Further reading: Read the full study by researcher Jessica Coria at the FRAM Centre for Future Chemical Risk Assessment and Management Strategies at the University of Gothenburg