We are facing a water crisis and it’s taking a toll on society. The cost of environmental inaction is staggering. The EU Commission estimates the cost of non-implementation of environmental laws at roughly €180 billion per year through pollution, waste and degradation.

So why have we seen little to no progress in the EU’s surface water health since 2010?

This September, Member States will come together to negotiate extensions to the Water Framework Directive (WFD), Europe’s primary surface and groundwater regulation. Despite having failed to meet its objectives for more than 10 years.

Europe’s Water Framework Directive

When the EU adopted the WFD back in 2000, it set a bold goal. By 2015, all European waters should reach ‘good’ ecological and chemical status. Fast forward ten years past that deadline, and the picture is bleak.

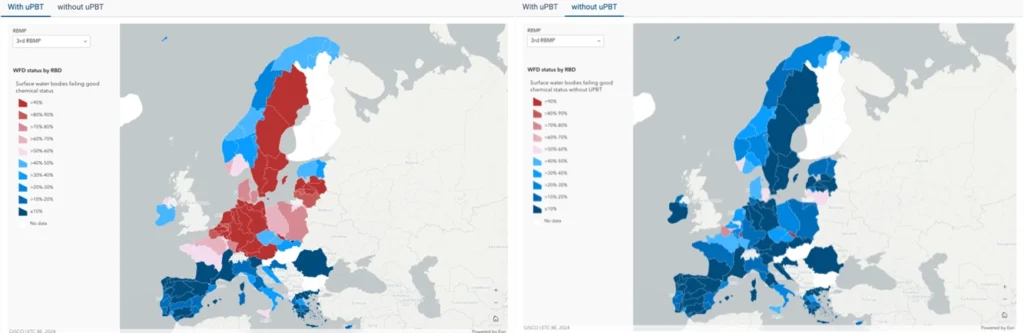

Today, less than 30% of Europe’s surface waters are in good chemical condition — and that number is getting worse, not better.

“Without [uPBT], 80% of surface waters could pass the chemical status test”

The reason for stalled progress? Persistent pollutants like PFAS, mercury and brominated flame retardants that linger for decades. These “forever chemicals” accumulate in rivers, lakes and groundwater, making it nearly impossible to deliver safe water or restore ecosystems.

Without these ubiquitous, persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic chemicals (or uPBT for short), 80% of surface waters could pass the chemical status test, according to the European Environment Agency (EEA).

Watering down regulations

Instead of taking decisive action to improve the water crisis and address chemical pollution, Member States have repeatedly pushed monitoring and compliance deadlines further into the future. First 2015, then 2027.

Now, countries want until 2039 to comply with newly proposed priority substances (including pesticides, pharmaceuticals and a new group of PFAS), with the possibility to derogate until 2051. Should Member States really be allowed to do nothing but monitor chemical pollutants in our water for another decade?

“Up to 35% of lakes, 60% of rivers and 100% of coastal and transitional waters in Europe exceed the regulatory threshold for PFOS”

In some cases, it’s even worse than we think. Many countries are still only assessing water quality against the first list of priority substances. This dates all the way back to 2008, with no legal requirement or enforcement to do more until 2027.

That means some Member States have already been effectively ignoring known pollutants for almost 20 years.

Take, for example, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) — just one type of PFAS added to the priority list in 2013. The EEA reports that up to 35% of lakes, 60% of rivers and 100% of coastal and transitional waters in Europe exceed the regulatory threshold for PFOS.

Yet Member States have no obligation to act on PFOS contamination until 2027.

Solving the water crisis starts with fixing the Water Framework Directive

Europe cannot meet its water goals by shifting timelines and adding exemptions. Adjusting the Water Framework Directive and related regulations this autumn is a chance to correct course. At minimum, we need to:

Stop kicking the can down the road

The new list of dangerous pollutants — including pesticides, pharmaceuticals and PFAS — must be included in the next water management cycle. Not delayed for another decade.

Keep strict timelines

The deadline for cleaning up the new pollutants should be set for 2033, without the option to postpone action until 2051. And where limits have already been made weaker, the existing 2027 deadline must still apply.

Address chemical mixtures

The EU must keep the proposed overall limits for pesticides and pharmaceuticals in water, and introduce modern monitoring methods that capture the combined effects of chemicals (effect-based monitoring).

Cover more PFAS

Right now, only 24 PFAS are counted in official limits — out of thousands. The EU’s own scientific committee recommends extending this to at least 100 PFAS, including TFA, which is already showing up everywhere in Europe’s waters.

It’s not too late. If the EU can step up now with bold commitments, our rivers, lakes and coastlines can recover — and future generations will inherit waters that are safe to drink out of, swim in and fish from.