Humans may not have the ability to reproduce naturally for much longer. By 2050, a large part of the global population will need assisted reproductive technology to procreate.

No, this is not the plot of a dystopian make-believe starring Clive “Children of Men” Owen or Elisabeth “The Handmaid’s Tale” Moss. These are the predictions of environmental and reproductive epidemiologist Shanna Swan, PhD, author of the recently published book Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race.

The fact that sperm count of men in Western countries has dropped more than 50% over the past 40 years is nothing new. But this discovery, revealed in 2017 by the very same Dr Swan, was – and still is – alarming.

Hormone-disrupting substances are to blame

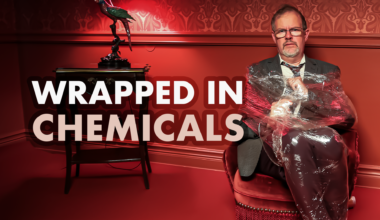

The cause for “Spermageddon”? Substances known as EDCs, Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals, which mimic hormones, thus fooling our cells. Phthalates (used to soften plastics), bisphenols (used to harden plastics), flame retardants and PFAS (a large group of substances also known as “forever chemicals”, since they don’t degrade) are all EDCs. They are also everywhere – in our food and water, children’s pyjamas, fire foam and couch cushions.

Another problem with EDCs is that we haven’t identified all substances that might interfere with our endocrinological system yet – let alone regulated them. This lack of knowledge and regulation inevitably creates a hotbed for “regrettable substitution”, making it easy for the manufacturing industry to switch from one banned chemical to an unregulated “cousin”.

That way, brands can boast about their “Bisphenol-A (BPA) free” baby bottles and “free from PFOA” frying pans, when all they might have done is to replace the regulated EDC with another, potentially even more harmful, bisphenol or PFAS chemical.

But surely there are greater threats to fertility than chemicals?

Critics of the studies on how EDCs affect human reproduction will argue that other factors, such as obesity and the decision to wait longer to have children, pose greater threats to human reproduction.

But Dr Swan dismisses these arguments by pointing out that lower sperm count and poorer egg quality have been found in young people with elevated levels of EDCs as well, and that chemically related fertility issues are in fact more common for younger women than older ones.

And while obesity is known to affect fertility, many EDCs are so called obesogens, believed to cause weight gain. It seems that the very same chemicals making it harder for us to reproduce are also making us fat.

The reproductive effects may be hereditary

To add insult to injury, the effect of EDCs is cumulative and may be passed on through generations. Reproductive geneticist Patricia Hunt, PhD, has conducted experiments on infant mice, exposing them to EDCs for just a few days. As adults, the mice produced fewer sperm, and so did their offspring. After three generations being exposed to EDCs, 1 in 5 of the male mice were infertile.

Even though these results do not necessarily apply to humans, Dr Hunt found the discovery particularly troubling, since she argues that humans are hitting the third generation of EDC exposure right about now.

We can turn this around

But there is hope, at least long-term. While Dr Hunt’s study shows that reproductive effects of EDCs may be hereditary, it also shows that it is possible to regain reproductive health after three or four generations – if the exposure stops.

This means that, assuming we take action now – today – our great-grandchildren, or possibly their children, will be able to escape “Spermageddon” and EDC induced infertility.

If we needed more reasons for faster, tougher and more far-reaching regulation on endocrine-disrupting chemicals, could this imminent threat against human reproduction be the straw that finally broke the camel’s back?